Portraits of Sibiel - A Community of Glances and Souls

Eugenia met her future mother-in-law and future husband, Gheorghe, in a train station when she was 18 years old. Gheorghe’s mother took such a liking to Eugenia during their chat on the platform that she asked Eugenia to live with them.

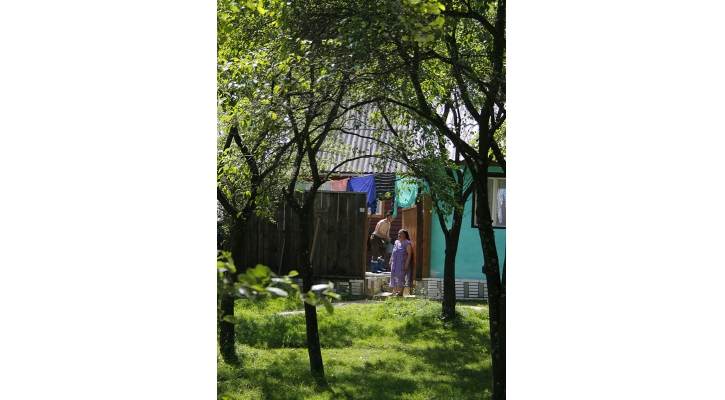

Eugenia and her family

Eugenia agreed. She’s lived in Sibiel ever since. At first Eugenia wrote home only that she was happy, safe, and married, but after two months, she finally told her mother that she was living in Sibiel. She was also pregnant.

Forty-three years and seven children later, Eugenia still lives and farms with Gheorghe in Sibiel. A lot has changed in the village during that time. Of Eugenia’s children, only one daughter remains in Sibiel. Eugenia’s other two daughters “own a lot of animals and land” in Bistrita Nasaud, and her two sons work in Austria and Germany. Two of the their children have died.

18-year-old Eugenia’s decision to move from town to the country and learn to farm seemed natural to her then, but it is all but unheard of now. Lured by modernization, her children and the children of her dwindling neighbors do just the opposite. Villages survive the loss of its younger generation in part by relying on the small money made from tourism. During my recent visit, I learned of Sibiel’s unusual tourism history. The village attracted visitors as early as the 1970s.

Father Zosim, a dream, and Sibiel’s tourism spark

The unique development of Sibiel’s tourism began with the village priest, Father Zosim Oancea. During his 15 years imprisonment under the communist regime, the Eastern Orthodox priest had a dream about a cathedral in Timisoara. He visited the cathedral after his release in 1963 and found a book there filled with pictures of icons. Inspired, he decided to collect glass icons at his new parish in Sibiel. There were six or seven icons in the church already, but he knew the village held many more.

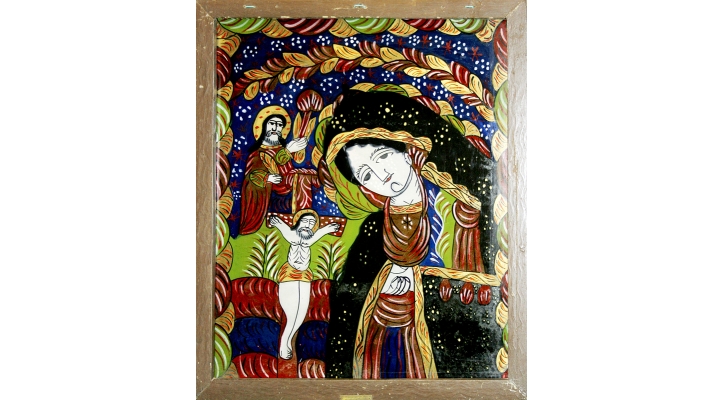

At one time, every girl in Sibiel had to own a glass icon before she could marry. Peasant farmers without any artistic training painted the icons using natural materials: lime for white, cobalt salts for blue, mud for yellow, salts of lead oxide and cuprite for red. The creation of an icon was deeply spiritual; the farmers prayed, fasted, and performed religious rites before beginning. Although the villagers clung to the traditional style (with Russian and Byzantine influences) and subject (mostly saints and biblical stories), they made the icons their own by dressing saints in regional costume and relating biblical hardship to their own struggle with the land.

Father Zosim asked villagers to donate icons that were lying around their homes in 1969. The community quickly collected almost 200 icons. Today the museum holds over 700 icons, many donated from other regions and even from Romanians living in Austria. When Father Zosim died in 2005, he had assembled the largest glass icon collection in Transylvania. Locals still regard him as a village hero and holy inspiration. His photograph hangs in the museum’s entrance.

In addition to visiting the glass icon museum, tourists have begun to frequent the village’s historic Eastern Orthodox church. The original painters of its iconographic frescoes incorporated a few Catholic saints to save it from destruction by the Austro-Hungarians during the 1760s, making the church an historic gem. Some tourists trek to the hilltop schit that lies outside the village. There, three monks live, farm, and work on construction of a new church next door to the one-room sanctuary the first monks of Sibiel built some 300 years ago.

There are 30 guesthouses in Sibiel today. I ate lunch at one of them. Like most of the guesthouses, it is owned by an outsider, not a villager. Its white paint is unchipped, its dining room is air conditioned, and its large stereo speakers blast American pop music from the ‘80s. Next to this guesthouse is a cluster of one-room wood and plaster structures, clotheslines, and a chicken coop. That is where Eugenia and Gheorghe live.

The realities of village life

We first spotted Eugenia from across the brook while we hiked the three kilometers to the schit several hours before. She had been lying on a rug she’d spread atop uncut grass. Still recovering from an appendix that burst last October, she prefers to make use of the cool breeze than stay inside. She motions for us to join her on the rug as we approach.

Eugenia didn’t know anything was wrong the day before her appendix burst. She thought the pain was something to do with her kidneys, so she spent the day working in the fields. Luckily, her son had not yet moved to Austria. When her pain became unbearable he could drive her the four kilometers to a neighboring village’s doctor (Sibiel has no doctor of its own). Only after her appendix had burst did Eugenia learn she’d even had appendicitis. By the time she’d gotten medical attention, the infection had spread to her lungs.

In a button-down dress and headscarf, Eugenia seems a breathing icon. Her hands remind me of the folded hands of Mary in one of the museum’s paintings. There, the aged skin represented Mary’s suffering. In this yard, I feel life has invaded the images I’d seen of paint and glass. The tangled grasses glow more vividly green even than the icons’ fields. Chickens squabble in the nearby coop. An ant traces Eugenia’s toenails, ankle, and calf.

Eugenia rubs her forehead when she talks about the health expenses. Her medicine alone costs 500 lei per month. She pays a neighbor 100 lei per month to drive her to the doctor—now that the children have entered their summer holiday, she cannot take the school bus. (Sibiel’s only school is a kindergarten. For further education, children must commute to other villages.) Eugenia feels lucky, though, that her son sends her money from Austria. She has fresh eggs and vegetables since the family still has a good patch of land at the village’s entrance, and she makes her own noodles for soup.

Surviving in a new Sibiel

Gheorghe is propped on his left leg and shirtless. His head is bald; his face is lined. He’s rolled black pants up above his ankles and sandals made of pink foam. He smokes a cigarette. There is an incision on his stomach. Gheorghe sits quietly while Eugenia talks—I sense this is their custom—but occasionally he tries to speak to me. I can understand some of his gestures. He spits on his sandal and flings it to the ground: he needs new shoes. Four fingers, then one pointed at himself: he has had only four years of schooling. Outstretched wing-arms and a glance in the direction of the Atlantic: he cannot believe that I have come all the way from America, in an airplane, and over an entire ocean. Sometimes I can understand only emotion, and Ana has to translate. He squints his eyes and pounds his fist in frustration. Ana translates for him, “It is so hard to live here.”

It wasn’t always this hard. Gheorghe used to work in a blanket factory. A Saxon woman taught him how to prepare the wool, and for 28 years he and other Sibiel farmers rode six kilometers each morning in a factory bus. Now the factory is closed, young villagers have moved away to find better work. Eugenia explains that the younger generation does not want to work the land. They want to be modern. “It’s a pity,” she says. The village has a lot of empty land waiting to be cultivated.

Farms have been disappearing from Sibiel over the last 50 years. Sibiel once had between 400 and 500 cows, about 300 horses, and 50 oxen, Ioan Petra, the village blacksmith (right), tells me. Then villagers started selling animals to open guesthouses. Now there are 10 cows, 32 horses, and no oxen at all. Petre has worked as the only blacksmith since 1966. He is 82 and retired, but he has no apprentice. The demand just isn’t there. Nevertheless, Petre assures me he appreciates the guesthouses and tourism, which he estimates bring one million lei into the village each year. He still repairs a few horseshoes and tools from time to time; sometimes he makes mini horseshoes as good luck charms for the village’s children.

Tradition that lives on

Eugenia had to spend last Christmas Eve in the hospital, but she could imagine exactly what was happening in Sibiel. The children were waking at 6 a.m. and dressing in traditional costumes to recite the oratii (religious poems) at the church. Then they clustered into groups that wove through the village streets singing carols. The young unmarried boys sang three songs for each family and collected money to organize a dance with the village girls.

Eugenia could be confident that the villagers were following the centuries old traditions, because they do for all religious holidays. As she relates customs for The Day of the Heroes and Jesus Rising, Saint Stephen’s Day, Holy Week, and Easter, Eugenia’s eyes glint with the relishing of each memory, each assurance that some things haven’t changed. Traditions like these sustain the inhabitants of Sibiel. Sometimes, Eugenia says with pride, even the tourists join the festivals, and the church teems with people.

Each winter, village women meet at Sibiel’s museum to paint new icons. They use the same natural materials that villagers mixed hundreds of years ago, but they paint upon fresh panes of glass and see old iconic images in new light. Praying and painting, they remember the holy Father Zosim’s words: “The icon has always seemed to me as a communion of glances and of souls in that goodness and beauty which unites us with and leads us to Him who has conquered the world.”

Sibiel’s museum houses icons of different ages side by side. Without dates or details about its maker, each icon seems a silent slide portraying some consistent rural spirit. Fresh generations, like new vines, cling to the aging lattice of the past. Through traditions and the land, paint and glass, the souls of the people of Sibiel commune not only with their maker, but with their predecessors too.

Text: Erika Lantz

Photos: Ana A. Negru