‘Do not let my village die’

What? A woman?” I’m at the top landing of the stairway in Sibiel’s small museum, and until now, the ascending line of photographs has shown only men—mayors, teachers, village priests.

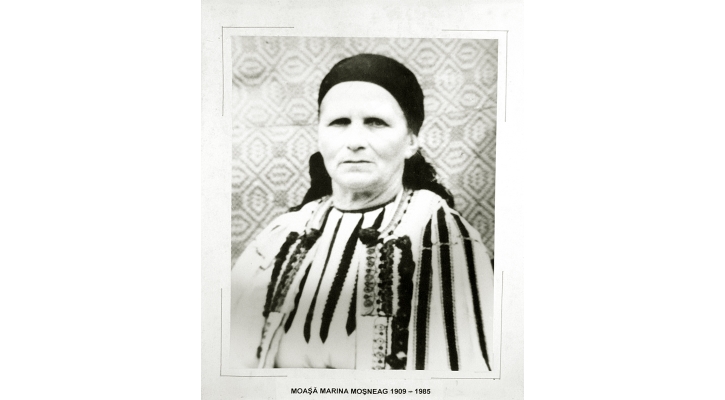

The Midwife from Sibiel

"What? A woman?” I’m at the top landing of the stairway in Sibiel’s small museum, and until now, the ascending line of photographs has shown only men—mayors, teachers, village priests.

“She was the midwife,” the guide says simply, and walks past. The inscription reads, “Moasa Marina Mosneag 1909-1985.” I wonder when this photo was taken. At first I can barely make out her eyes, hidden as they are in shadow. They seem slim wells, her pupils like submerged stones that glisten only when one peers deeper. These eyes are set above strong cheekbones in a weathered face. She has wound her scarf tightly, pinning her hair flat to her head. No frills for her besides the stripes of her blouse and traditional vest.

I imagine Marina Mosneac walking home at night after a birth. She’d pass the scattered houses alone with the knowledge that her village’s population had increased by one. Marina Mosneac knew each villager from the first moment of life. When she met a neighbour on the street, she saw the wriggling newborn, still red and small in her arms. She watched babies grow into adults, whom she in turn helped through pregnancies and new births. She saw mothers die, children die. She watched the children that lived move away to cities and “opportunity.” She grew up in Sibiel during World War I and II, lived through the collectivization of farms under communism, and died just four years before Revolution. More than any mayor framed below her, she was the guardian of Sibiel’s history. The photograph’s starkness - the tight, black triangle of her scarf, the white skin, the geometric wallpaper behind - makes me feel that the midwife is stripped bare in front of me. Her eyes, defiant, then strip me. I meet her stare. She is telling me something important:

‘Do not let my village die’.

Footsteps and the creak of stairs snatch me away from such rumination. The reality is that this is just a photograph. It is flat and framed and hanging on a wall. My companions have moved on to the museum’s next room, but I can’t seem to leave this image, because I’ve realized something: rural Romania needs a midwife.

Romania’s villages need someone who remembers them as children, when their first settlements began. Someone to help them bear more fruit and be witness to a still vibrant, still growing history. Someone who cares that they live.

Each Romanian born in a village has the potential to be this metaphorical Midwife of Villages, but most fail. They leave to find jobs and never return, looking back (and sending money) to the village only as long as their parents still live. No one waits to see whether Romanian villages will collectively survive or suffocate.

No one, that is, until now.

The newly founded NGO featured in our ‘Rural Development’ section will form an unprecedented team called The Most Beautiful Villages of Romania to look over and rejuvenate villages. Made up of villagers themselves, the association wants nothing but to keep rural Romania alive. “Tourism agency” would be a gross misnomer. The association is a community of potential “village midwives,” all eager to continue the tradition of rural Romania but aware that they cannot do it alone. They will work together to save the past.

This magazine, too, forms a part of the collective Midwife. I urge you, read on. Become a ‘moasa’, the next witness of the rebirth of the Romanian village.

by Erika Lantz